Ginger

Ginger

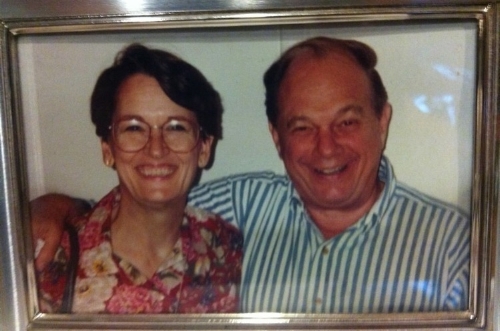

My grandmother is the only person

who ever fixed my hair.

She would braid my long locks most days —

summer days, school days, holidays —

usually French.

Her tan, arthritic hands,

free of all jewelry,

would weave my brunette wavy tresses

into a manageable mane,

quickly learning

that my hair was unruly, wild,

had a mind of its own

and would crawl its way out of a braid

unless wet or slathered in gel.

While she twisted, turned, and pulled,

she would teach me all the French words

for my ballet lessons

or regale me with stories,

taking me back to her own childhood

in middle-of-nowhere Arkansas

after the Great Depression.

Hours spent braiding her own hair

or playing jacks and gin rummy

with her maiden aunts

with whom she had to share a bed at night,

Aunt Kat’s uneven polio-altered body

protruding under the thin quilts.

While her brothers — now doctors —

played baseball with the neighborhood boys

and had a room of their own to share.

I sat quietly and listened

through the soft pulls on my hair,

enjoying the stories.

I would pick a spot on the wall

and stare at it,

like a ballerina in a loop of endless pirouettes

until the wall disappeared entirely

and I was there, on the front porch,

playing cards,

waiting for my aunts to take me to the library,

my stack of books by the door

next to the empty milk bottles.

My grandmother can no longer braid my hair.

Her fingers have become too gnarled

by arthritis, sun damage,

old age.

I rub her hands beneath mine.

Her thin, tan skin moving easily,

too easily,

over her bones.

She lets me play with her veins,

moving the blood in the blue lines

up and down,

up and down,

emptying and refilling.

But the blood,

the blood always comes back.

Copyright © 2025 Emily Andry. All rights reserved.